I attended the recent ‘Digital Health Re-Wired’ conference at Birmingham’s NEC last week. There was a lot of talk about AI – in fact I think the term pretty much featured on every stand and in every stage presentation at the conference. People are excited about AI and wherever you work in healthcare AI is coming to a clinical information system near you…

At this point I need to declare an interest – I absolutely hate the term Artificial Intelligence – I think it is a totally misleading term. In fact I’m pretty sure that there is no such thing as artificial intelligence – it is a term used to glamorise what are without doubt very sophisticated data processing tools but also to obscure what those tools are doing and to what data. In medical research hiding your methods and data sources is tantamount to a crime…

An Intelligent Definition

So what is artificial intelligence? It refers to a class of technologies that consist of certain types of algorithm paired with very large amounts of data. The algorithms used in AI are variously called machine learning algorithms, adaptive algorithms, neural networks, clustering algorithms, decision trees and many variations and sub-types of the same. Fundamentally however, they are all statistical tools used to analyse and seek out patterns in data – much like the statistical tools we are more familiar with such as linear logistic regression. In fact the underpinning mathematics of a learning algorithm such as a neural network was invented in the 18th century by an English Presbyterian Minister, Philosopher and Mathematician – The Reverend Thomas Bayes. Bayes’ Theorem found a way for a statistical model to update itself and adapt its probabilistic outcomes as it is presented with new data. The original adaptive algorithm – which has ultimately evolved into to today’s machine learning algorithms – which are given their power by being hosted on very powerful computers and being fed very very large amounts of data.

The other ingredient that has given modern machine learning tools their compelling illusion of ‘intelligence’ is the development of a technology called large language models (LLMs). These models are able to present the outputs of the statistical learning tools in natural flowing human readable (or listenable) narrative language – i.e. they write and talk like a human. Chat-GPT being the most celebrated example. I wrote about them about 5 years ago (The Story of Digital Medicine) – at which point they were an emerging technology but have since become mainstream and extremely effective and powerful.

Danger Ahead!

Here lies the risk in the hype – and the root cause of some of the anxiety about AI articulated in the press. Just because something talks a good talk and can spin a compelling narrative – doesn’t mean it is telling the truth. In fact quite often Chat-GPT will produce a well crafted beautifully constructed narrative that is complete nonsense. We shouldn’t be surprised by this really – because the source of Chat-GPT’s ‘knowledge’ is ‘The Internet’ – and we all have learned that just because its on the internet doesn’t mean its true. Most of us have learnt to be somewhat sceptical and a bit choosy over what we believe when we do a Google search – we’ve learnt to sift out the ads, not necessarily pick out the first thing that Google gives us and also to examine the sources and their credentials. Fortunately Google is able to give us quite a lot of the contextual information around the outputs of its searches that enables us to be choosy. Chat-GPT on the other hand hides its sources behind a slick and compelling human understandable narrative – a bit like a politician.

The Power of Data

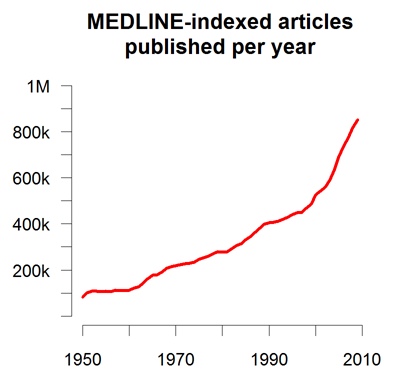

In 2011 Peter Sondergaard – senior vice president at Gartner, a global technology research and consulting company – declared “data eats algorithms for breakfast”. This was in response to the observation that a disproportionate amount of research effort and spending was being directed at refining complex machine learning algorithms yielding only marginal gains in performance compared to the leaps in performance achieved by feeding the same algorithms more and better quality data. See ‘The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Data’

I have experienced the data effect myself – back in 1998/99 I was a research fellow in the Birmingham School of Anaesthesia and also the proud owner of an Apple PowerBook Laptop with (what was then novel) a connection to the burgeoning internet. I came across a piece of software that allowed me to build a simple 4 layer neural network – I decided to experiment with it to see if it was capable of predicting outcomes from coronary bypass surgery using only data available pre-operatively. I had access to a dataset of 800 patients of which the majority had had uncomplicated surgery and a ‘good’ outcome and a couple of dozen had had a ‘bad’ outcome experiencing disabling complications (such as stroke or renal failure) or had died. I randomly split the dataset into a ‘training set’ of 700 patients and a ‘testing set’ of 100. Using the training set I ‘trained’ the neural network – giving it all the pre-op data I had on the patients and then telling it if the patients had a good or a bad outcome. I then tested what the neural network had ‘learned’ with the remaining 100 patients. The results were ok – I was quite pleased but not stunned, the predictive algorithm had an area under the ROC curve of about 0.7 – better than a coin toss but only just. I never published, partly because the software I used was unlicensed, free and unattributable but mainly because at the same time a research group from MIT in Boston published a paper doing more or less exactly what I had done but with a dataset of 40,000 patients – their ROC area was something like 0.84, almost useful and a result I couldn’t come close to competing with.

Using AI Intelligently

So what does this tell us? As practicing clinicians, if you haven’t already, you are very likely in the near future to be approached by a tech company selling an ‘AI’ solution for your area of practice. There are some probing questions you should be asking before adopting such a solution and they are remarkably similar to the questions you would ask of any research output or drug company that is recommending you change practice:

- What is the purpose of the tool?

- Predicting an outcome

- Classifying a condition

- Recommending actions

- What type of algorithm is being used to process the data?

- Supervised / Unsupervised

- Classification / Logistic regression

- Decision Tree / Random Forrest

- Clustering

- Is the model fixed or dynamic? i.e. has it been trained and calibrated using training and testing datasets and is now fixed or will it continue to learn with the data that you provide to it?

- What were the learning criteria used in training? i.e. against what standard was it trained?

- What was the training methodology? Value based, policy based or model based? What was the reward / reinforcement method?

- What was the nature of the data it was trained with? Was it an organised labeled dataset or disorganised unlabelled?

- How was the training dataset generated? How clean is the data? Is it representative? How have structural biases been accounted for (Age, Gender, Ethnicity, Disability, Neurodiversity)?

- How has the model been tested? On what population, in how many settings? How have they avoided cross contamination of the testing and training data sets?

- How good was the model in real world testing? How sensitive? How specific?

- How have they detected and managed anomalous outcomes – false positives / false negatives?

- How do you report anomalous outcomes once the tool is in use?

- What will the tool do with data that you put into it? Where is it stored? Where is it processed? Who has access to it once it is submitted to the tool? Who is the data controller? Are they GDPR and Caldecott compliant?

Getting the answers to these questions are an essential pre-requisite to deploying these tools into clinical practice. If you are told that the answers cannot be divulged for reasons of commercial sensitivity – or the person selling it to you just doesn’t know the answer then politely decline and walk away. The danger we face is being seduced into adopting tools which are ‘black box’ decision making systems – it is incumbent on us to understand why they make the decisions they do, how much we should trust them and how we can contribute to making them better and safer tools for our patients.

An Intelligent Future

To be clear I am very excited about what this technology will offer us as a profession and our patients. It promises to democratise medical knowledge and put the power of that knowledge into the hands of our patients empowering them to self care and advocate for themselves within the machinery of modern healthcare. It will profoundly change the role we play in the delivery of medical care to patients – undermine the current medical model which relies on the knowledge hierarchy between technocrat doctor and submissive patient – and turn that relationship into the partnership it should be. For that to happen we must grasp these tools – understand them, use them intelligently – because if we don’t they will consume us and render us obsolete.

Recent Comments